Habitats in our Watersheds

Longleaf Pine Forests:

Upland habitats are home to many species of plants and animals and play a critical role in water infiltration.

Wetlands:

These important barriers retain excess nutrients and pollutants, trap sediment, and protect us from flooding and wave energy.

Habitat Change:

Development, agriculture, and other human land uses alter the natural landscape.

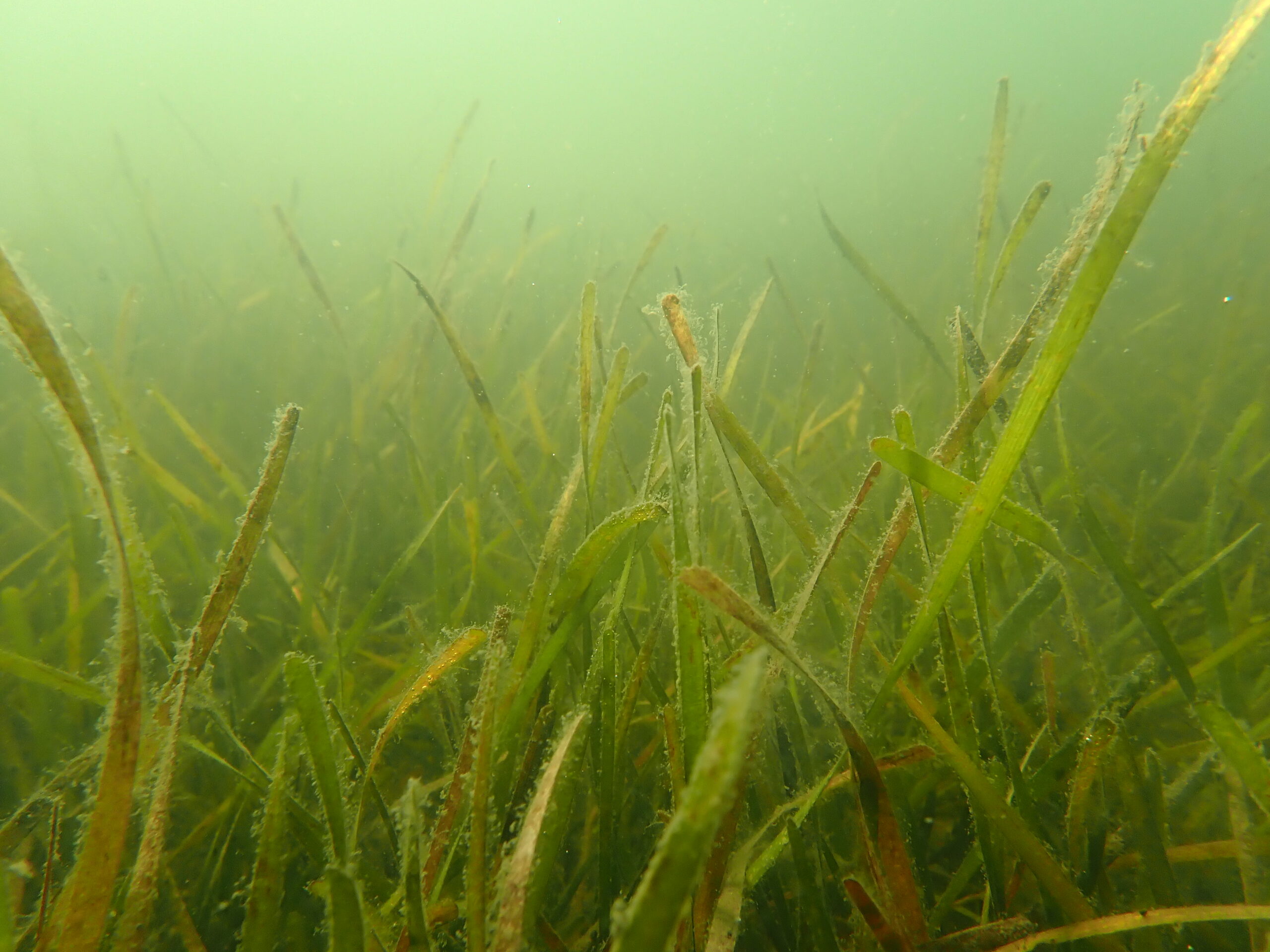

Seagrass Beds:

Submerged grasses filter water, provide nursery and foraging grounds for wildlife, store carbon, and stabilize sediments.

Oyster Reefs:

These ecosystem engineers provide habitat to fish and shellfish, protect shorelines, and filter water for particles and nutrients.

Pensacola Bay Watershed

Oyster Reefs

Oysters are ecosystem engineers that provide habitat for fish, shellfish, and birds. They also help improve water quality by filtering water and stabilizing shorelines. Pensacola Bay oysters are culturally and economically significant and once supported a thriving oyster industry.

- Declining since the 1980s due to poor water quality and overfishing

- We no longer have enough oysters to support wild harvest

- Due to these declines, the oyster industry has turned to oyster aquaculture (farming)

- There is hope – the community came together to develop a plan and initial funds have been secured to restore up to 1,500 acres of oyster habitat in the next 10 years

980 acres of oyster reef found in 2010

480 acres of oyster reef found in 2021

The Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (FDACS) is responsible for regular bacterial testing of coastal waters to ensure wild and farmed oysters in the bay are safe to eat.

- Bacterial monitoring in the bay started in 1985

- Long term bacteria level trends determine which areas are approved or prohibited for oyster harvesting

- Additional short term closures may occur in response to environmental conditions

- The prohibited harvest area was expanded in 2022 due to consistently high bacteria levels, impacting aquaculture operations

- Bacteria concentrations have been increasing in middle Escambia Bay (just south of I-10) since 2015

- Efforts are underway to determine bacteria sources and remediate them

Pensacola Bay oyster reefs: 2010 & 2021

Pensacola Bay Fecal Coliform 1985-2024

Help restore our oysters!

- Volunteer to help build Vertical Oyster Gardens (VOGs)

- Support restaurants that participate in oyster shell recycling programs

- Buy locally farmed oysters (when available)

- Support investments for water quality improvements

- Donate to help restore our reefs

Seagrass Beds

Seagrasses are plants that grow entirely underwater in marine and brackish waters. They are important nursery habitats for many species, stabilize our shores, and filter our waters. Poor water quality and propeller scarring have historically led to seagrass declines, but in recent years, we have seen stable seagrass coverage.

Mapping efforts are completed every few years to assess the health and coverage of seagrass beds. Why are some years missing data for certain segments of the Bay? Monitoring costs money! Researchers and agencies sometimes have limited resources to complete mapping for the entire bay. We anticipate collecting new seagrass mapping data in 2025 that will be included in the 2027 report.

Lower Pensacola Bay

- Large declines from 1960s to 1992 (~630 acres lost)

- Conditions improved from 1992 to 2012 with an additional 120 acres, but coverage is only about half of what it was in 1960

- Though 2022 maps show some losses, this is likely due to shifting methodologies and higher resolution information, rather than actual losses

Santa Rosa Sound

- Large declines from 1960s to 1980s (about half lost)

- Relatively stable from 1980s to 2022, ranging from 2,800 to 4,600 acres

- Though 2022 maps show some losses, this is likely due to shifting methodologies and higher resolution information, rather than actual losses

Pensacola Bay Seagrass Surveys 1960-2022

Santa Rosa Sound Seagrass Surveys 1960-2022

Be Seagrass Aware!

- You can help prevent propeller scarring — trim up your motor when boating over shallow seagrass beds — your motor will thank you too!

- It’s our goal to complete regular seagrass mapping of Pensacola and Perdido Bays. We need your help to make it happen. Donate here!

Wetlands

Wetlands are important transition zones between terrestrial and aquatic environments. They protect shorelines by buffering wave energy, filter water by trapping sediments and pollutants, and provide habitat for thousands of plants and animals. There are many kinds of wetlands including marshes, bogs, and swamps. The majority of wetlands in our watersheds are located along main river systems and represent large areas of relatively undisturbed habitat.

- Wetland coverage appears stable over 20 years, but underlying trends show localized losses, potentially due to development in coastal counties

- These calculations are based on satellite-derived data, which may not accurately represent true wetland conditions and can be influenced by factors such as vegetative cover, seasonal water presence, or sensor limitations

Protect our wetlands!

- Keep shorelines soft and living – consider a natural shoreline instead of seawalls or bulkheads

- Maintain vegetated barriers that act as buffers along wetland edges and streambanks

- Properly dispose of pet waste, toxic chemicals, and oil

- Practice smart fertilizer use

Pensacola Bay Watershed Wetlands (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wetlands Inventory)

Longleaf Pine Forests

Longleaf pine forests support over 1,200 plant and animal species and play an important role in the history and culture across the Southeastern U.S.

- These pine forests once covered more than 90 million acres until the 1800s, when the logging industry decimated these forests

- Prior to logging in the 1800s, these forests covered >90 million acres across the Southeast

- Less than 3% of the historical range remains in the Southeast

- These ecosystems are fire dependent and historically burned regularly from lightning strikes

- Fragmented habitat has reduced the natural burning cycle and prescribed fire is used as a management technique to maintain habitat for important species like the red-cockaded woodpecker and gopher tortoise

- Natural reforestation and restoration are helping to recover these forests and the wildlife that depend on them

- A subpopulation of the red-cockaded woodpecker within the Blackwater River and Conecuh National Forests reached recovered status in 2024 (Longleaf Alliance)

Pensacola Bay Watershed Longleaf Pine Occurrences

Protect our longleaf pine forests!

- Landowners – longleaf resources for forest management

- Support land conservation to help maintain natural habitats

- Consider a lasting legacy and preserve your land in perpetuity

Habitat Change

Natural habitats and landscapes are altered as humans shape the land to fit our needs. Land use is continually changing among types, resulting in land conversions that can alternate over time (e.g., forested area is developed, developed area is later reforested). These changes alter habitat availability, water quality and flow, and potentially threaten wildlife and human health.

- There is an overall increase in habitat change across the watershed, but this is a negative change because we are losing our natural habitats

- Forest is the main land cover type in our watershed

- Coastal areas are experiencing rapid development

- Over the last 20 years (2001-2021):

- Escambia County (FL)

- 35% increase in developed land

- 11% increase in forests

- 18% loss of wetlands

- Okaloosa County (FL)

- 72% increase in developed land

- 5% increase in forests

- ~8% loss of agricultural land

- Santa Rosa County (FL)

- 72% increase in medium intensity development

- 53% increase in high intensity development

- 7% increase in forests

- 2% loss of wetlands

- Escambia County (FL)

How you can help

- Smart city planning can help reduce urban sprawl

- Talk to your local elected officials! Well-written land development codes can help reduce the impacts of development

- Support land conservation to help maintain natural habitats

- Consider a lasting legacy and preserve your land in perpetuity

Pensacola Bay Watershed National Land Cover Database 2001-2021

Pensacola Bay Watershed Conservation Lands

Perdido Bay Watershed

Seagrass Beds

Seagrasses are plants that grow entirely underwater in marine and brackish waters. They are important nursery habitats for many species, stabilize our shores, and filter our waters. Poor water quality and propeller scarring have historically led to seagrass declines, but in recent years, we have seen stable seagrass coverage.

Mapping efforts are completed every few years to assess the health and coverage of seagrass beds. Why are some years missing data for certain segments of the Bay? Monitoring costs money! Researchers and agencies sometimes have limited resources to complete mapping for the entire bay. We anticipate collecting new seagrass mapping data in 2025 that will be included in the 2027 report.

Lower Perdido Bay

- Following a period of decline from 1987 to 2015, there was an increase of ~200 acres in 2020

- Though 2022 maps show some losses, this is likely due to shifting methodologies and higher resolution information, rather than actual losses

Big Lagoon

- Relatively small declines in coverage from 1960 to 2010

- Coverage has remained stable around 500-600 acres since 1960

- Though 2022 maps show some losses, this is likely due to shifting methodologies and higher resolution information, rather than actual losses

Lower Perdido Seagrass Surveys 1940-2022

Big Lagoon Seagrass Surveys 1960-2022

Be Seagrass Aware!

- You can help prevent propeller scarring — trim up your motor when boating over shallow seagrass beds — your motor will thank you too!

- It’s our goal to complete regular mapping of Pensacola and Perdido Bays. We need your help to make it happen. Donate here!

Wetlands

Wetlands are important transition zones between terrestrial and aquatic environments. They protect shorelines by buffering wave energy, filter water by trapping sediments and pollutants, and provide habitat for thousands of plants and animals. There are many kinds of wetlands including marshes, bogs, and swamps. The majority of wetlands in our watersheds are located along main river systems and represent large areas of relatively undisturbed habitat.

- Wetland coverage appears stable over 20 years, but underlying trends show localized losses, potentially due to development in coastal counties

- These calculations are based on satellite-derived data, which may not accurately represent true wetland conditions and can be influenced by factors such as vegetative cover, seasonal water presence, or sensor limitations

protect ouR wetlands!

- Keep shorelines soft and living – consider a natural shoreline instead of seawalls or bulkheads

- Maintain vegetated barriers that act as buffers along wetland edges and streambanks

- Properly dispose of pet waste, toxic chemicals, and oil

- Practice smart fertilizer use

Perdido Bay Watershed Wetlands (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wetlands Inventory)

Longleaf Pine Forests

Longleaf pine forests support over 1,200 plant and animal species and play an important role in the history and culture across the Southeastern U.S.

- These pine forests once covered more than 90 million acres until the 1800s, when the logging industry decimated these forests

- Prior to logging in the 1800s, these forests covered >90 million acres across the Southeast

- Less than 3% of the historical range remains in the Southeast

- Natural reforestation and restoration are helping to recover these forests

- These ecosystems are fire dependent and historically burned regularly from lightning strikes

- Fragmented habitat has reduced the natural burning cycle and prescribed fire is used as a management technique to maintain habitat for important species like the red cockaded woodpecker and gopher tortoise

Protect our longleaf pine forests!

- Landowners – longleaf resources for forest management

- Support land conservation to help maintain natural habitats

- Consider a lasting legacy and preserve your land in perpetuity

Perdido Bay Watershed Longleaf Pine Occurrences

Habitat Change

Natural habitats and landscapes are altered as humans shape the land to fit our needs. Land use is continually changing among types, resulting in land conversions that can alternate over time (e.g., forested area is developed, developed area is later reforested). These changes alter habitat availability, water quality and flow, and potentially threaten wildlife and human health.

- There is an overall increase in habitat change across the watershed, but this is a negative change because we are losing our natural habitats

- Forest is the main land cover type in our watershed

- Coastal areas are experiencing rapid development

- Over the last 20 years (2001-2021):

- Baldwin County (AL)

- 54% increase in medium intensity development

- 65% increase in high intensity development

- 6% loss of wetlands

- 6% loss of agricultural land

- Escambia County (AL)

- 44% increase in medium intensity development

- 36% increase in high intensity development

- 13% increase in forest

- 18% loss of wetlands

- 7% loss of agricultural land

- Baldwin County (AL)

how you can help

- Smart city planning can help reduce urban sprawl

- Talk to your local elected officials! Well-written land development codes can help reduce the impacts of development

- Support land conservation to help maintain natural habitats

- Consider a lasting legacy and preserve your land in perpetuity

Photo: Darryl Boudreau, NWFWMD

Photo: PPBEP

Photo: PPBEP

Perdido Bay Watershed National Land Cover Database 2001-2021

Perdido Bay Watershed Conservation Lands